Clothes are the first silent curriculum of womanhood.

Words by Alex Gwaze (Curator)

Questions by Alex Gwaze & Joanne Peters (Image Coach, Philanthropist)

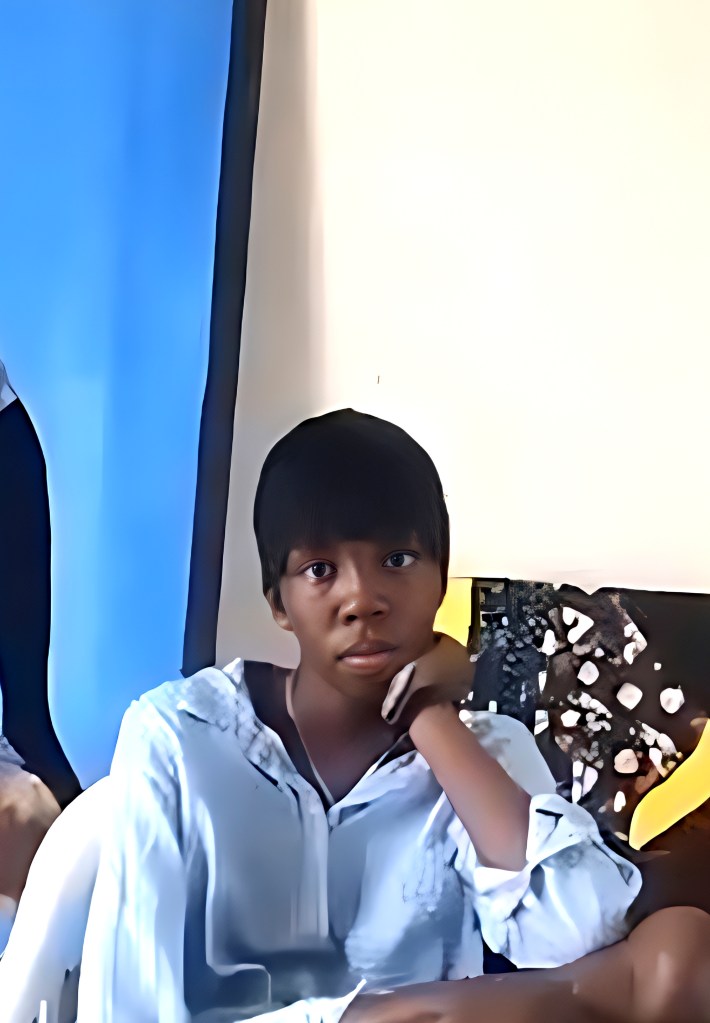

Before the artist known as Shamie Art creates anything, she sorts through the ghosts of garments that long ago outlived the promises they were made for. Born Sinqobile Shamiso Dube and celebrated for her fearless fabric language, the three-time National Arts Merit Awards–nominated artist begins every project with a quiet ritual: unearthing the wreckage of second-hand clothes that spill across her studio floor. Each piece has travelled further than most people ever will. A T-shirt faded to the shade of memory. A blazer from a company that died years ago. Jeans stitched in an Asian factory, shipped to Europe, discarded in America, and finally resurrected in Zimbabwe. By the time these clothes reach her hands, they have survived continents, closets, bodies, and entire economies.

This river of clothing is part of a global system few stop to question. Nearly 70–80% of the world’s used clothes end up on African soil — not through generosity, but through a long history disguised as one. Western countries once called it “charity,” a soothing narrative that turned excess into virtue and African markets into moral laundromats. Today, this global waste has been transformed into a vast informal economy that sustains street vendors, tailors, and everyday people parsing through open bales in search of profit, novelty, or simply possibility. Shamie sees something else entirely.

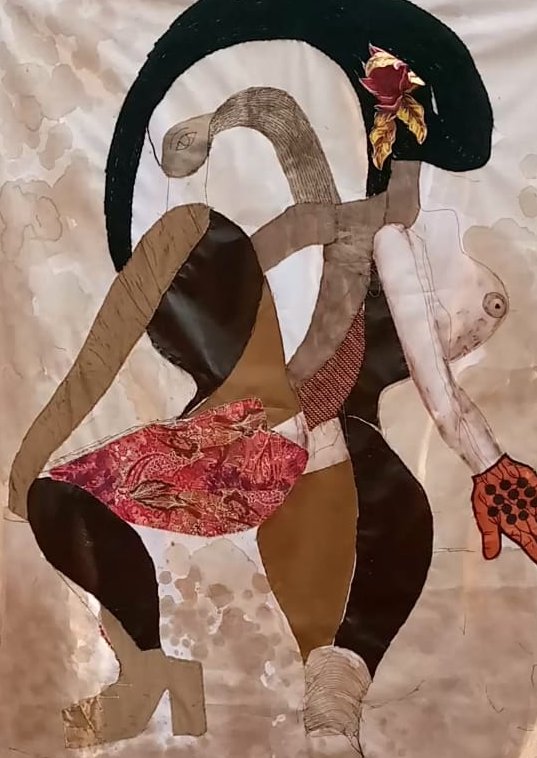

Trained at Mzilikazi Art and Craft Centre, she treats these garments as archives — raw evidence of how African women navigate a world designed without them in mind. For generations, women across the continent have inherited silhouettes that never matched their bodies, fabrics that never matched their climates, and styles that never imagined their cultures. In Shamie’s hands, these mismatched relics become a new language: one that articulates the lives, labour, joys, burdens, dreams, and silent negotiations stitched into womanhood.

Her ability to translate fabric into art has carried her into exhibitions across the country, from the National Gallery’s Connections to the European Union Culture Fund’s Canvas of My Identity. But it was her solo exhibition A Woman’s Yoke that marked the turning point — nearly 70 works, each one an excavation, recoded and exhibited as evidence of past and future human behaviour.

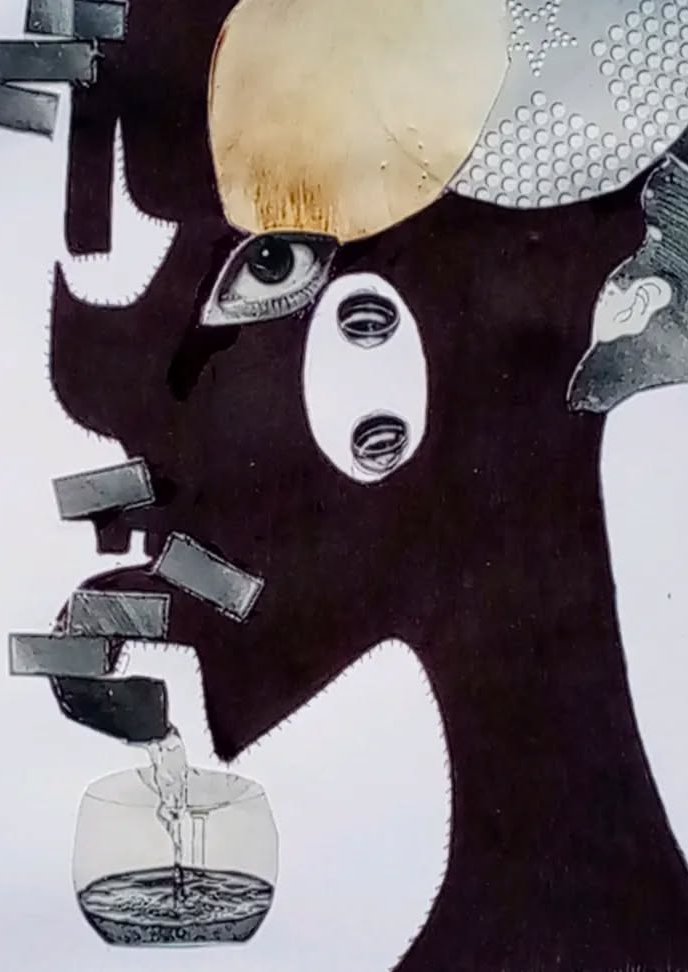

Where many artists romanticise clothing, Shamie interrogates it. She approaches fabric like an archaeologist: digging through layers, decoding meaning. A dress becomes evidence of pleasure. A handbag, the weight of a deferred dream. A pair of heels, a lineage of inherited pain. A magazine advert, a deception. Through her, fashion is no longer shallow — it reveals the afterlife of the ideas we once wore, the stories clothes collect long after their first wearers leave them behind. For her, clothes don’t die when we stop wearing them. They simply start telling the truth.

AG: When you first started, you were known for your pen-drawn portraits. These days, I’ve seen you transition to soap on fabric, which can easily be rubbed off. Is being able to draw well still important to the kind of art you make today?

SD: Yes! I still apply those principles of art in my process now, and I also bend a few (laughs). The difference is that when I was drawing with pens, it was more structured and precise. That meant I was, to a certain extent, controlled, rigid, and a bit restricted in expressing my creativity. But with these fabric characters that I create, I am flexible and don’t take myself too seriously. However, I still have to make sure that proportions are correct. I still ensure my work has that depth of perspective I used to achieve with “traditional” drawing. So practical drawing is less central now, but the foundation of sketching and arranging compositions still guides my work.

JP: How do you decide which materials — fabrics, patterns — deserve a second life, not just recycled, but reborn as art?

SD: It’s hard to explain. For me, fabrics carry characters and a voice, you know. I don’t know how to explain it, but my process is: I do my sketch and then head straight to my pile of discarded clothes and start picking. If you ask me what I would be searching for, the answer would most likely be, “I don’t know, but when I see it, I will know” (laughs). Most of the time, the first fabric I pick determines the rest. It’s kind of like when you are ripping apart a jersey — you only have to start with the first thread, and the rest of the garment unravels fluidly.

AG: On that idea of second lives: many Africans’ wardrobes are filled with garments sourced from open-air second-hand markets.

SD: Well, the rise of second-hand clothing in Africa is a problem because not all the clothes are bought or reused. So I often wonder where that excess goes. When I make my art from fabrics, I am playing a small part in raising awareness about this issue, and making sure those unwanted clothes are put to good use. But I honestly think it’s just a raindrop in the ocean; there are tonnes of unwanted and unused clothes here, and like I mentioned, I often wonder where it all ends up. Because it ends up in Africa, people stop asking real meaningful questions about this process.

AG: You just brought up some interesting questions that I have to admit will change how I think about “mabhero.” You often say, “clothes carry memory.” What is your earliest memory of a piece of clothing?

SD: I made you think twice, so you could also consider me a conceptual artist as well (laughs). For me, from an early age, fabric has always been a language I used to communicate where I am and where I want to be, and now I tell stories of other people too. That comes from my earliest memory of a piece of clothing, which was a bag I made from my grandmother’s old tablecloth. The tablecloth was light blue with a golden dog on it. I didn’t have a lot of clothes at that time; we went through a difficult period at home to the extent that my sister and I had to share a pair of flip-flops. Our white school shirts were also our dressing-up, fancy clothes. So I decided that since I couldn’t afford a proper bag, I would make one and carry it to church the next day — and I did. I felt very confident carrying my “new” bag. That old tablecloth was my very first fabric artwork that communicated my desire to have more in life one day.

JP: For women, bags, shoes, hair, jewellery — objects signal personality, status, or roles. Is that multiplicity what you were exploring in your exhibition A Woman’s Yoke?

SD: A Woman’s Yoke was definitely looking at the different facets that serve a woman. I focused on her thoughts, fantasies, secrets, fears, emotions, relationships, friendships, roles, and responsibilities — telling different stories of women. The whole point was to highlight the immense capabilities that women possess, which are often taken for granted, even by women themselves. However, as we were preparing for the exhibition, a friend of mine researched the word “yoke.” A yoke is a wooden beam used to harness animals, but it can also be a part of a garment. So the whole reason for the exhibition was to tell a story about this dynamic: the metaphorical woman’s load.

AG: Part of that “yoke” is appearance right? Particularly in terms of public perception — and how do you navigate that tension?

SD: Appearance is important for everyone, not just women; it’s the masks we put on daily. We tell stories to ourselves and teach people how they should see or view us through our clothes. And for my work, I believe half the job is done, or half the story is told, by the outfits I dress my characters in. Without hearing the character’s voice, people can tell a lot about them and make a judgement through those outfits. (laughs) It’s funny, I was talking to my friend, and we noted that a lot of people who are not wealthy love in-your-face flashy brands, as if to make up for something. On the other hand, most wealthy people dress in simple ways and quiet colours, usually with no visible brands, as if to conceal something. I’m not saying this is how everyone is; just my observation.

AG: I think you are right about that. You enjoy people-watching, don’t you? Some inspiration for A Woman’s Yoke came from hours spent in your hair salon listening to stories. Was there a story that you couldn’t — or chose not to — translate into art?

SD: Yes I do! There were so many stories, but one stood out — a lady whose partner was a gang leader. Yoh! She worked at a bar, and every time she smiled at customers, she would get beaten. The abuse continued until one day she felt her back crack. It’s sad. After beating her, her boyfriend gave her money to come and get her hair plaited into a ponytail. When she arrived at my salon, she asked if I could do her lying down. It was a strange request, but I thought it was probably fatigue from her late-night shifts. Little did I know. She didn’t disclose the truth until after I had done her hair. She told me, “Please tie the braids into a ponytail and please make it tight.” When I had done that, she looked at herself in the mirror and said, “He told me to tie up my hair after beating me. When he comes in the evening, he said round two; he wants to pull my hair.” I couldn’t, and still can’t, make artwork about this story because I always wonder what happened to her. I hope her story changed.

AG: That is a horrific reality that has to change. I feel you kind of subconsciously put her in your work. Your work often features both beautifully shaped figures and distorted, monstrous, or phantasmagoric bodies. What role does the female body play in your work?

SD: In some artworks, it’s just me escaping into my imagination. On the other hand, it feels comfortable to create female characters because it’s familiar. For me, the female body represents me. I cannot tell stories about a man because I have never been in a male body, so if I am to tell a story of a man, there has to be a woman somewhere in the artwork; otherwise, it feels distant and disconnected.

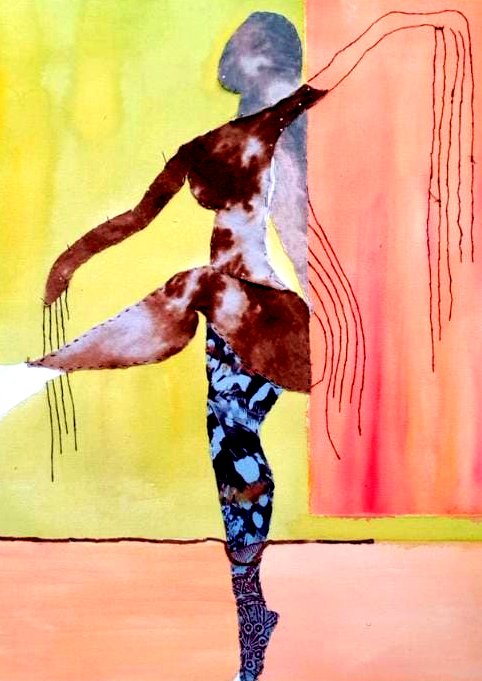

JP: I’m particularly drawn to your eye-catching, primary-like colours in the backgrounds of your work. Do these colours shape the energy, mood, and ideas of your pieces?

SD: Those bold colours have meaning. Yellow represents healing according to my spiritual belief. Blue is water, cleansing, and purity. Red is fire, passion, sometimes warning. I love how the colours light up the room (laughs). You can’t help but feel light looking at some colours, even though the subject matter might be heavy. But the first fabric determines everything, including the background. The background is the seal of the artwork. Once done, I have emptied myself of the ideas and energy for that piece.

JP: Speaking of eye-catching work, you painted the Steers Restaurant mural on Fife Street in Bulawayo. To end off, what does it feel like to move your art from private galleries into public spaces?

SD: I did that artwork with a good friend. It was an opportunity to grow and learn. Creating works for private galleries and collectors is different from works that art lovers and non-art lovers will see, appreciate, or not. I’ve been privileged that all my works are exhibited in quality spaces, but seeing my hands create something as precise and clean as that mural for everyone was a good tap on the shoulder. You know what ties it all together though — the gallery works and murals were made by the hands I was blessed with. Everything gels when you use your hands well (laughs).

On a continent where hand-me-downs are both family tradition and global waste, the wardrobe is never neutral. Fast fashion has created a loop of aspiration and shame: African women chase trends designed continents away, wear what someone discarded, yet style it with pride, all while carrying the unspoken pressure to look “put together.” Shamie doesn’t reject this — she intervenes, exposing the emotional labour stitched into clothes, turning fabric into testimony and fashion into artifact. The irony is that the very garments she transforms often make their way back to the West, landing in private collections from Dubai to Stockholm, Toronto to London.

Follow Shamie at: @shamieart