String words together — and meaning is born.

Words by Alex Gwaze (Curator)

Questions by Elspeth Chimedza (Writer, Content Creator) and Alex Gwaze

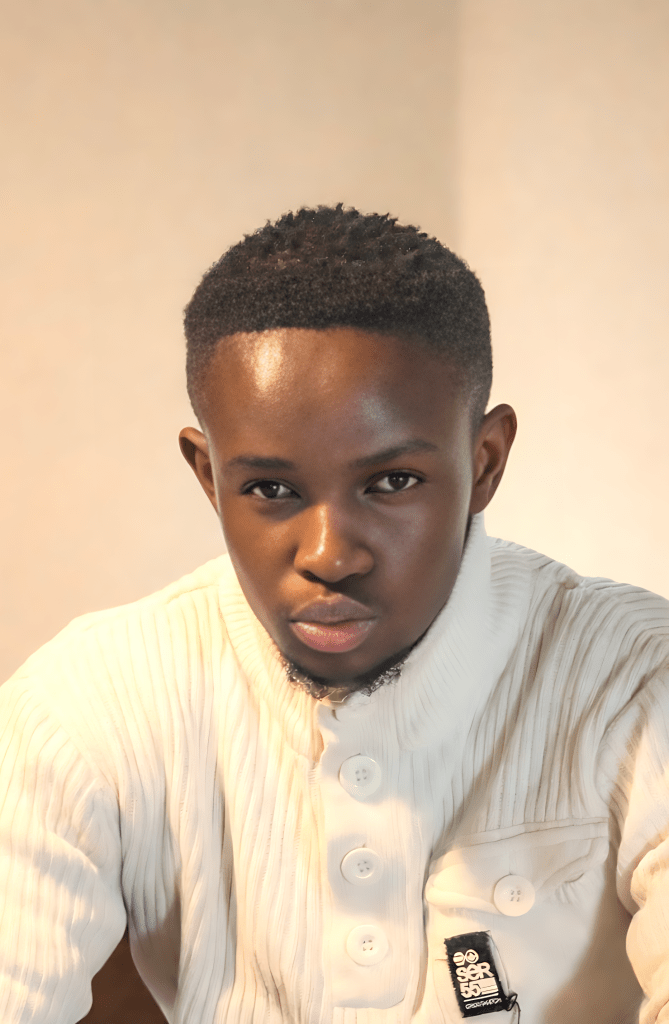

Engineering might seem far removed from writing, but for Mandela Washington Fellow Tyrone Nkululeko Takawira, they are twin mechanisms for crafting meaning. Born in Zimbabwe and trained as a mechanical engineer at Ashesi University in Ghana, Takawira moves seamlessly between the rigid geometry of machines and the fluid cadence of language. He is, in effect, the piston between force and emotion.

Tyrone is a global prize winner of the Wole Soyinka International Essay Competition and the Kalahari Igby Prize in Botswana, as well as a finalist in both the George Floyd Short Story Competition (UK) and Bergen LitFest Competition (Norway), Takawira’s true calibration lies in the power of syntax. His work channels African injustices into the global arena, translating the aftertaste of colonialism that lingers in identity, trauma, intimacy, memory, and pleas. That tension — what you feel even now — is what makes his voice so arresting.

Consider these lines from his own writing: “We are the beating drums of a tribe. We are black unkempt hair, roots that meander like our rivers. We are the voices of heroes; the souls that broke silence and injustice.” This is not the dry, encyclopaedic straight line one might expect from a mechanic. It is resonant, longing, flexible, and full of rupture. It channels the lyricism of poetry while carrying the urgency of someone for whom identity is neither inherited nor stable — but forged by culture, not metal. Perhaps that is why his tone remains disciplined and precise, yet conscious of the labour involved in birthing a self not defined by victimhood.

“I am inspired by the concept of ‘leading through words’ — and seek to provide important commentaries on issues that matter. To represent not only observation, but solution. I am driven by the beauty of voice,” he explains. Takawira writes of rape, incest, and suicide — and their architecture — in numerous anthologies and magazines, including Brittle Paper, Black Lives’ Anthology (Nottingham Writers Studio), Global Commons (Fall 2022), Eboquills, and The Kalahari Review. What is remarkable is not merely the subject matter, but how he refuses to soften it with euphemism. He confronts it head-on, translating what he learned in classrooms and laboratories into pertinent questions and possible answers.

His self-published poetry collection, His Words. His Empire. His Reign, offers an interesting segue into how language can be positioned as power, and how text can expand territory. Reading it reminds us that words, like machines, carry weight, momentum, and force—and that language, when engineered with purpose, becomes both tool and testament: built to resonate, to move, and to endure.

EC: You trained as a mechanical engineer but became known for your words, not machines. Do you see writing as another kind of engineering?

TT: Yes, most definitely. Both emphasise the beautiful power of creation. I like to think of writing as the engineering of the mind, heart, and soul – and ultimately, of society. We often become the stories we tell of ourselves – to ourselves. There’s a saying: “Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” From a historical standpoint, you can think of antisemitism, racism, and systemic prejudice – all of which existed because one group’s story made another seem inferior. Stories are the foundation of our social contract – what we deem morally acceptable or not. It is left versus right. It is good and evil. The engineering we use to examine ourselves and communicate. As someone who has been both the scientist and the writer, I’m not sure which one is more powerful.

EC: Winning the Wole Soyinka Essay Competition put you on the map. Soyinka, a Nobel Prize laureate, is as much an activist as a writer. His words are powerful.

TT: That’s an interesting dynamic, you know. In my case, my work took a major shift during the pandemic. Before then, it was mainly personal – a form of catharsis. But when the “new norm” was forced on us, I recognised the need to empower others far from me with words, especially at a time of isolation. In that chaos, I wrote I Am Because You Are, which spoke about individual and collective sacrifice, and the need to put differences aside because we had a common enemy. The essay offered both perspective and hope and further motivated me to keep writing – not only for myself but for others.

AG: Turning the attention away from Soyinka for a bit, Zimbabwe has given the world Dambudzo Marechera, Charles Mungoshi, and Tsitsi Dangarembga. Do you think they’re regarded as they should be?

TT: I do think they are remembered as they should be, especially at home. They put Zimbabwe on the global map for literary excellence, alongside NoViolet Bulawayo and Petina Gappah. Dambudzo was a rare and enigmatic talent. Mungoshi mastered storytelling in both English and Shona, captivating a nation. Dangarembga is the kind of writer I aspire to be – brave on and off the page. Truly impactful writing stands for justice. Their recognition at home feels limited to academia or niche literary circles. Tsitsi is perhaps the most recognised globally, but I believe more intentional work must be done to fully commemorate all our literary geniuses in all their diversity and boldness. This might reflect a culture that doesn’t quite fully value literature yet.

EC: You could be right. The Mandela Washington Fellowship gathers young African leaders in the U.S. to learn and connect. They recognised you for your literary prowess. From your experience there, what does it really take to lead?

TT: I genuinely believe true leadership always stems from authenticity – being so deeply passionate and ingrained in your craft that it becomes who you are. If you are truly passionate, you will naturally draw people toward you. Skills like communication and assertiveness can be learned, but authenticity cannot. There is a hunger in the world for people who are unapologetically themselves – the mavericks, the rebellious, the geniuses. Those who stand out because they refuse to blend in. This rare and valuable quality is the hallmark of leadership.

AG: Let’s talk “empire.” Specifically, your book His Words. His Empire. His Reign. What empire are you building with your words?

TT: Mmm, that is a great question. Our realities are shaped by language and the stories we tell. We don’t fully recognise just how much we are reflections of our beliefs and convictions – and these are shaped by our most prevailing narratives. I want to create an empire that demonstrates the true power of words to shape worlds. I’d like to create timeless work – short stories, essays, interviews – that will be spoken about long after I’m gone. Work that sparks global dialogue and influences thought. For me, “empire” means legacy, inspiration. To “reign” means to stay in a continuous state of writing – true to the mission, and most importantly to myself.

EC: You’ve written about trauma, abuse, and survival — and you don’t flinch. How do you hold that weight without letting it break you?

TT: Sometimes the sheer emotion and rawness of the work can be heavy. In those moments, I remind myself these are stories worth telling. There is always someone out there who resonates with the trauma and the pain. It is my obligation to speak, even if the stories are not my own. I remind myself there is a strong need to break the trauma of silence – to release, to heal – through expression.

AG: Despite its heaviness, your work feels global in reach but rooted in Africa. How do you write for the world without sanding down the edges of home?

TT: That’s a good question! Every time I write, I try to speak to a global audience without restricting myself. But because I am African by birth and experience, the African lens always fine-tunes the vision – which is good. Travelling extensively has helped me write from a global perspective still rooted in Africanism. It’s also important to let the story tell itself, I believe. Over-editing can dilute authenticity, so you should let it be as much as possible. When you tell a story as perfectly and truthfully as it can be told, it will resonate across borders.

AG: You’ve called your style of writing an act of “excavation.” What’s the deepest thing you’ve dug up in yourself?

TT: We are going even deeper (laughs). I am at my most selfless when I am writing. And by that, I mean most of the time, I’m telling stories I’ve not personally experienced, which is both liberating and challenging. Interestingly, I only started getting real recognition when I stopped writing for me and turned my focus to us – to stories society resonates with. So the deepest thing I’ve dug up is my ability to use writing to give back. To step outside of myself, my beliefs, my biases, and tell the truth, especially about stories that need to be told as truthfully and perfectly as they should be told.

EC: That was deep. It makes me think — how do you survive as a writer in the age of shrinking attention spans? I mean, social media is the opposite of excavation — fast, loud, forgettable.

TT: You’re on point. That’s something many creatives struggle with. But it’s important to adapt – to see social media not as an enemy but as an ally. A 3,000-word short story can be as rewarding as a 300-word flash fiction. A spoken-word piece can be as powerful as a written poem. Social media has made everything fast but has also given us a larger platform than those before us. It’s a tool to transform and elevate your art and your voice. The key is to adapt and leverage technology in pursuit of creative mastery.

AG: Zimbabwe is a place where silence often feels safer. So, lastly, how can you elevate your voice in this kind of environment?

TT: Tough question. I’m not going to sugarcoat it – that’s an art I’m still learning to master. I often provide social commentary but still feel I border on being “politically correct.” I’ve learned to be subtle in my messaging, especially around politics, religion, and sexuality. You can be bold without offending, but the lines can be blurry when you are passionate about a cause. But I’m watching and learning from creatives and activists like Namatai Kwekweza and Tsitsi Dangarembga. Their courage to move against the grain is immensely inspiring, even in the face of opposition.

It seems engineering and writing are very much alike. As much as we would love to simply express ourselves and say what we want, to whom, and when we want, we must be mindful of the link between force and motion. We must design something grounded in principle — easy to maintain, using materials or words that do not create friction, yet are familiar enough to be universally understood. It is a science; it is mathematical — a calculation of risk, of offence, and of intention. But ultimately, it all requires a good engine, a good heart that keeps the movement alive. That’s why Tyrone writes as if rebuilding what history dismantled, using syntax as scaffolding and empathy as blueprint. In his world, stories are not escapes; they are the fuel — the fire that moves us, heals us, and reminds us that truth, like machinery, must be tended to, if we want the world to keep running.

Follow Tyrone at @iiam.greatness